‘Thucydides came closer than Herodotus in the Search for ‘historical truth’?’

Proposition:

– Alexander Roberts

– Julius Guthrie

– Lynette Mitchell

Opposition:

– Jack West-Sherring

– Davide Scarpignato

– Chris Farrell

Chair: Elaine Sanderson

After the resounding success of the first Classics Society debate of this year on whether ancient texts should be exempt from modern views about sexual harassment, the motion this year centred around an issue more overtly academic; the sort of topic on which we ourselves might write an essay. I for one can’t see the Guild coming out with a #HerodotusFatherOfLies campaign any time soon. Nevertheless, this by no means diminished the debate, with arguments hotly made on all fronts and an excellent turnout, helped in part by the presence of several students of Exeter College who are studying Thucydides as a part of their Classical Civilisation course; in this way the debate was an excellent outreach activity on behalf of the society.

After a brief summary of the essential facts about both men and their works, replete with beard jokes, from Chris Farrell, the debate was kicked off by Alexander Roberts on team Thucydides. In accordance with the formal rules of this sort of debate, the proposition defined the motion as best they could; Alex defined truth as ‘an accurate account of events that occurred in the respective works of each author, which provided an understanding of what these events meant’. From this basis, Alex set out some of the key facts which would re-emerge later as important themes: Thucydides’ rigorous methods of fact-checking, his annalistic chronology, obsession with truth and accuracy, and the very fact that he was contemporary with his events all play a part in Thucydides’ reputation as the founder of scientific history. While Thucydides sought to write objectively, Herotodus is more concerned with preserving great deeds, and is making a biased inquiry. Accordingly, Thucydides is a much fairer writer than Herodotus, who was writing about some events far before his time and telling stories. Alex also brought up another key theme; speeches. Whereas Thucydides openly admits that his speeches are compositions, and admits that he can only try his best, Herodotus is silent on the subject and presents us with ‘deceptive’ attempts at passing off what was really said.

Next, Jack West-Sherring rose to defend Herodotus. Jack cleverly avoided lingering on the disadvantages of Herodotus by pointing out significant flaws in Thucydides, namely his presentation of a straight account. For example, Thucydides says that the cause of the Peloponnesian War was Spartan fear of the growth of Athenian power, but this is just his theory. Thucydides gives us this and obscures his reasoning and his sources. Herodotus on the other hand spells everything out for us and lets us make up our own mind – another remerging theme. Furthermore, Jack pointed out that Thucydides was far more biased than Herodotus, given his election to generalship in Athens in 424 and education there. In contrast, Herodotus was raised bestride Asia and Greece, and was thus a much more open minded individual who gave us a holistic view of the world. Furthermore, Thucydides was clearly biased against Pericles, whom Thucydides, as a member of the elite, wants to portray as the ruler of Athens. Thus, Thucydides distorted truth as well. Jack concluded that the task of his team was to show that Herodotus was not inferior to Thucydides, and so – citing Paul Cartledge – concluded that they were on a level playing field.

In rebuttal spoke Julius Guthrie. In a well structured speech, Julius explained to us why Thucydides was closer to truth. Firstly, his speeches and style was largely speaking truthful, from a certain point of view: although they are compositions, they accurately reflect how the speeches were received at the time through his explanation afterwards of precisely this. Secondly, Julius argues that in antiquity it was clear that Thucydides was closer to the truth. Citing Polybius, Cicero. Plutarch – infamously opposed to Herodotus and his malice – and Lucian, Julius showed how each of them praises Thucydides as a paragon of truth and Herodotus as a failure, precisely because he was not like Thucydides. Lastly, Julius emphasised that Herodotus was interested in telling stories rather than true events, such as the Persian constitutional debate, or most of books 1-4.

Davide’s response was perhaps a little defeatist – he first argued that there was no real way to compare the two authors (“apples and pears”) because they were just too different, but then brought back a little fire to the debate by arguing that – if the opposition insisted – Herodotus was clearly superior. Davide focussed on Herodotus’ method; picking up Jack’s point, the argument was that Herodotus – in a way much closer to modern practise – exercises in the reader a sense of a critical viewpoint, whereby we are trained to question for ourselves, rather than just be spoon-fed by Thucydides, reminding us also that Herodotus probably recited much of his work to the general public.

At this point the debate was handed over to the members of staff, the ‘big guns’. Prof. Lynette Mitchell simultaneously took the debate up to new levels but also brought the house down with her perceptive argument that Thucydides transcends facts in order to focus on the big picture, at the expense of the quote ‘I have passions for dead men’. According to Lynette’s impassioned speech, it didn’t matter whether Thucydides’ speeches were fabricated or not – he is instead telling us what happens to man when man descends to a state of war. What does war do to common people? How does it change what they do, and how they treat their peers? Lynette showed us how Thucydides depicts the Athenians’ decline to such a state whereby they could call it ‘natural law’ that the strong should rule over the weak. Events themselves and sequence of events are subordinate to the bigger issues; what it really means for mankind to be mankind.

In response to this, Chris Farrell – having cunningly armed himself with a PowerPoint for visual aids – set out to rebuke some of the arguments made previously, in many ways tying together many of the themes of the debate. Firstly, the distinction that Thucydides was contemporary whereas Herodotus was much later than his events ignores completely the Archaeology – the start of Thucydides’ work, where he deals with many of the same issues as Herodotus. Secondly, Herodotus’ inclusion of the divine is not simply to make a better story, but to show us what people really believed and how they saw the world, whereas such things are obscured by Thucydides. Furthermore, according to Chris, we should not take seriously Plutarch’s criticisms, as he’s more a defender of his Boeotian ancestors – slighted by Herodotus – than an accuser. What’s more, some of the ridiculed aspects of Herodotus’ account actually turn out to be true, such as sheep with obscenely huge tails, which do indeed exist. Chris also argues that Thucydides was devious in his hiding of his historical process; we want to know why he made that interpretation, rather than just having the interpretation. Herodotus allows us to look at the world of the past and construct our own reality, rather than just forcing us to accept his, as Thucydides did – thus, he concluded, Herodotus came closer to historical truth.

And so ended the speeches from the speakers. The floor was opened up to questions, both from the teams to each other and from the audience to the teams. Amid vehement exchanges, freshly coined words (‘Why does Herodotus fantasticate so much?’), and not an insubstantial amount of repetition it has to be said, the debate was fruitfully elevated once more by Lynette and Chris. Lynette pointed out that we couldn’t really say that either Herodotus or Thucydides was interested in historical truth as we conceive of it, as they were trying to do something altogether different. Chris added that the question itself had modernist overtones, and that we had to bear in mind that in some sense it is unfair of us to enforce our values of what “History” should be on the ancients.

Along these lines, a standout question from the floor was from Charles Pelham-Lane, who argued that the Greek word for ‘truthful’ – ἀληθης – is literally ‘α-‘, which denotes a negation, + ‘λήθη’, which meant ‘forgetting’. Thus, for these authors, ‘historical truth’ means something like ‘not forgetting’. Davide responded by saying that actually it was ‘α-‘ + a form of ‘λανθάνω’, which means something more like ‘concealing’: thus ‘ἀληθης’ means something which is ‘unconcealed’, or ‘true’. It turns out that the ancients themselves believed the former, whereas modern linguistics prefer the latter explanation. Nevertheless, Charles’ excellent wider point that we must engage with the Greek terms rather than our own was well received.

As all good things must, the debate was thence finished, and a vote was taken. After some potentially spurious counting it was proclaimed that the proposition carried the day by 1 vote (18:17). Overall it was a fantastic debate with very engaging speakers, and taught us more about not only Herodotus and Thucydides, but also a lesson about how we tackle any ancient text – it is perhaps a more favourable inquiry to judge such a text on its own terms, rather than apply modern notions. Well done to all.

This debate was kindly written up by Tom McConnell, 3rd Year Classics Student, 3rd Year SSLC Representative, and Classics and Ancient History Editor for The Undergraduate Journal (http://www.theundergraduateexeter.com/)

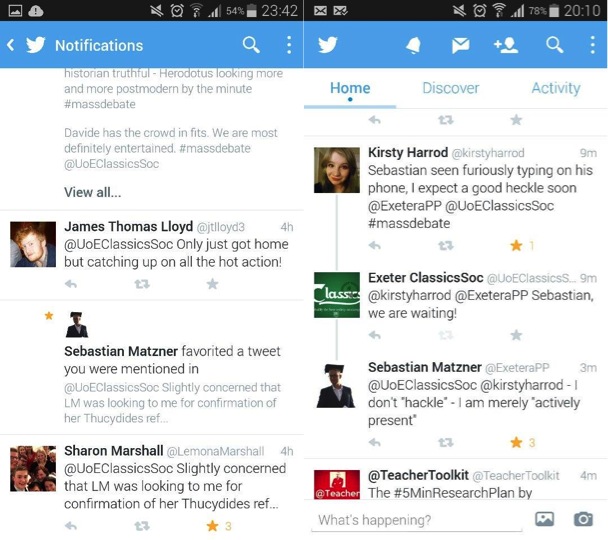

The debate attracted a great deal of attention from students and staff on Twitter!